Aurora

Aurora is a natural light in the sky. Occur near both poles of the planet with magnetic field. On earth, you need to go between 10°-20° degree from the geomagnetic poles, and wait until dark to easily observe. Its colors can vary from red to blue, but the most well known color is green.

The content of this article is excerpted from Wikipedia. It exist here as a placeholder for layout development purpose.

An aurora, sometimes referred to as a polar light, is a natural light display in the sky, predominantly seen in the high latitude (Arctic and Antarctic) regions. Auroras are produced when the magnetosphere is sufficiently disturbed by the solar wind that the trajectories of charged particles in both solar wind and magnetospheric plasma, mainly in the form of electrons and protons, precipitate them into the upper atmosphere (thermosphere/exosphere), where their energy is lost. The resulting ionization and excitation of atmospheric constituents emits light of varying colour and complexity. The form of the aurora, occurring within bands around both polar regions, is also dependent on the amount of acceleration imparted to the precipitating particles. Precipitating protons generally produce optical emissions as incident hydrogen atoms after gaining electrons from the atmosphere. Proton auroras are usually observed at lower latitudes. Different aspects of an aurora are elaborated in various sections below.

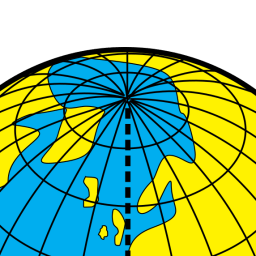

Occurrence of terrestrial auroras

Most auroras occur in a band known as the auroral zone, which is typically 3° to 6° wide in latitude and between 10° and 20° from the geomagnetic poles at all local times (or longitudes), most clearly seen at night against a dark sky. A region that currently displays an aurora is called the auroral oval, a band displaced towards the nightside of the Earth. Day-to-day positions of the auroral ovals are posted on the internet. A geomagnetic storm causes the auroral ovals (north and south) to expand, and bring the aurora to lower latitudes. Early evidence for a geomagnetic connection comes from the statistics of auroral observations. Elias Loomis (1860), and later Hermann Fritz (1881) and S. Tromholt (1882) in more detail, established that the aurora appeared mainly in the “auroral zone”, a ring-shaped region with a radius of approximately 2500 km around the Earth’s magnetic pole. It was hardly ever seen near the geographic pole, which is about 2000 km away from the magnetic pole. The instantaneous distribution of auroras (“auroral oval”) is slightly different, being centered about 3–5 degrees nightward of the magnetic pole, so that auroral arcs reach furthest toward the equator when the magnetic pole in question is in between the observer and the Sun. The aurora can be seen best at this time, which is called magnetic midnight.

In northern latitudes, the effect is known as the aurora borealis (or the northern lights), named after the Roman goddess of dawn, Aurora, and the Greek name for the north wind, Boreas, by Galileo in 1619. Auroras seen within the auroral oval may be directly overhead, but from farther away they illuminate the poleward horizon as a greenish glow, or sometimes a faint red, as if the Sun were rising from an unusual direction.

Its southern counterpart, the aurora australis (or the southern lights), has features that are almost identical to the aurora borealis and changes simultaneously with changes in the northern auroral zone. It is visible from high southern latitudes in Antarctica, South America, New Zealand, and Australia. Auroras also occur on other planets. Similar to the Earth’s aurora, they are also visible close to the planets’ magnetic poles. Auroras also occur poleward of the auroral zone as either diffuse patches or arcs, which can be sub-visual.

Planetary auroras

Both Jupiter and Saturn have magnetic fields much stronger than Earth’s (Jupiter’s equatorial field strength is 4.3 gauss, compared to 0.3 gauss for Earth), and both have extensive radiation belts. Auroras have been observed on both, most clearly with the Hubble Space Telescope. Uranus and Neptune have also been observed to have auroras.

The auroras on the gas giants seem, like Earth’s, to be powered by the solar wind. In addition, however, Jupiter’s moons, especially Io, are powerful sources of auroras on Jupiter. These arise from electric currents along field lines (“field aligned currents”), generated by a dynamo mechanism due to the relative motion between the rotating planet and the moving moon. Io, which has active volcanism and an ionosphere, is a particularly strong source, and its currents also generate radio emissions, studied since 1955. Auroras also have been observed on the surfaces of Io, Europa, and Ganymede, using the Hubble Space Telescope. Auroras have also been observed on Venus and Mars. Because Venus has no intrinsic (planetary) magnetic field, Venusian auroras appear as bright and diffuse patches of varying shape and intensity, sometimes distributed across the full planetary disc. Venusian auroras are produced by the impact of electrons originating from the solar wind and precipitating in the night-side atmosphere. An aurora was also detected on Mars, on 14 August 2004, by the SPICAM instrument aboard Mars Express. The aurora was located at Terra Cimmeria, in the region of 177° East, 52° South. The total size of the emission region was about 30 km across, and possibly about 8 km high. By analyzing a map of crustal magnetic anomalies compiled with data from Mars Global Surveyor, scientists observed that the region of the emissions corresponded to an area where the strongest magnetic field is localized. This correlation indicates that the origin of the light emission was a flux of electrons moving along the crust magnetic lines and exciting the upper atmosphere of Mars.

The brown dwarf star LSR J1835+3259 was discovered to have auroras in July 2015, the first extra-solar auroras discovered. The aurora is a million times brighter than the Northern Lights, mainly red in colour, because the charged particles are interacting with hydrogen in its atmosphere. It is not known what the cause is. Some have speculated that material maybe being stripped off the surface of the brown dwarf via stellar winds to produce its own electrons. Another possible explanation is an as-yet-undetected planet or moon around the dwarf, which is throwing off material to light it up, as is the case with Jupiter and its moon Io.

author