Polar Bear

Polar bear is a cute white creature live in North Pole. To survive extream cold temperature, it has to develope large thick fur to cover its entire body. Its baby must be born with large body or it will be freeze to death. Favorite diet are fish and seals.

The content of this article is excerpted from Wikipedia. It exist here as a placeholder for layout development purpose.

The polar bear (Ursus maritimus) is a carnivorous bear whose native range lies largely within the Arctic Circle, encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is a large bear, approximately the same size as the omnivorous Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorffi). A boar (adult male) weighs around 350–700 kg (772–1,543 lb), while a sow (adult female) is about half that size. Although it is the sister species of the brown bear, it has evolved to occupy a narrower ecological niche, with many body characteristics adapted for cold temperatures, for moving across snow, ice, and open water, and for hunting seals, which make up most of its diet. Although most polar bears are born on land, they spend most of their time on the sea ice. Their scientific name means “maritime bear”, and derives from this fact. Polar bears hunt their preferred food of seals from the edge of sea ice, often living off fat reserves when no sea ice is present. Because of their dependence on the sea ice, polar bears are classified as marine mammals.

Because of expected habitat loss caused by climate change, the polar bear is classified as a vulnerable species, and at least three of the nineteen polar bear subpopulations are currently in decline. For decades, large-scale hunting raised international concern for the future of the species but populations rebounded after controls and quotas began to take effect. For thousands of years, the polar bear has been a key figure in the material, spiritual, and cultural life of circumpolar peoples, and polar bears remain important in their cultures.

Naming and etymology

Constantine John Phipps was the first to describe the polar bear as a distinct species in 1774. He chose the scientific name Ursus maritimus, the Latin for ‘maritime bear’, due to the animal’s native habitat. The Inuit refer to the animal as nanook (transliterated as nanuq in the Inupiat language). The Yupik also refer to the bear as nanuuk in Siberian Yupik. The bear is umka in the Chukchi language. In Russian, it is usually called бе́лый медве́дь (bélyj medvédj, the white bear), though an older word still in use is ошку́й (Oshkúj, which comes from the Komi oski, “bear”). In French, the polar bear is referred to as ours blanc (“white bear”) or ours polaire (“polar bear”). In the Norwegian-administered Svalbard archipelago, the polar bear is referred to as Isbjørn (“ice bear”).

The polar bear was previously considered to be in its own genus, Thalarctos. However, evidence of hybrids between polar bears and brown bears, and of the recent evolutionary divergence of the two species, does not support the establishment of this separate genus, and the accepted scientific name is now therefore Ursus maritimus, as Phipps originally proposed.

Biology and behaviour

Physical characteristics

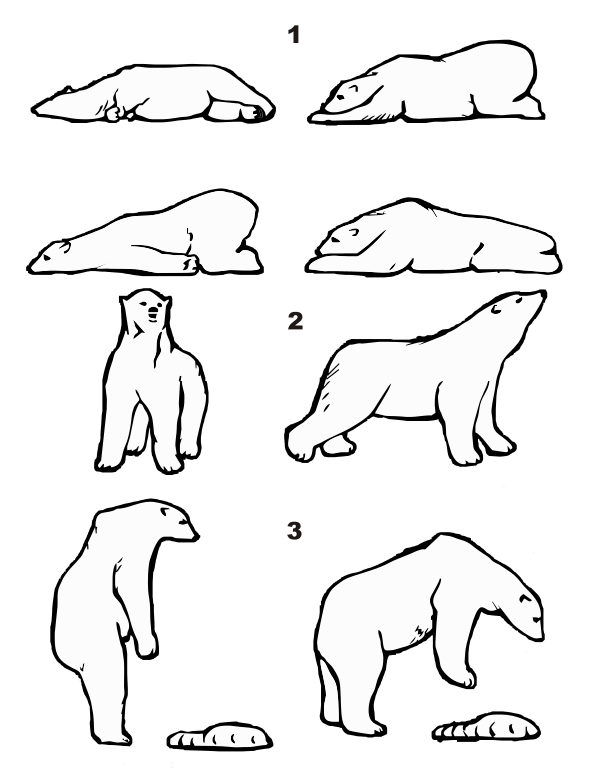

The only other bear of a similar size to the polar bear is the Kodiak bear, which is a subspecies of brown bear. Adult male polar bears weigh 350–700 kg (772–1,543 lb) and measure 2.4–3 metres (7 ft 10 in–9 ft 10 in) in total length. The Guinness Book of World Records listed the average male as having a body mass of 385 to 410 kg (849 to 904 lb) and a shoulder height of 133 cm (4 ft 4 in), slightly smaller than the average male Kodiak bears. Around the Beaufort Sea, however, mature males reportedly average 450 kg (992 lb). Adult females are roughly half the size of males and normally weigh 150–250 kg (331–551 lb), measuring 1.8–2.4 metres (5 ft 11 in–7 ft 10 in) in length. Elsewhere, a slightly larger estimated average weight of 260 kg (573 lb) was claimed for adult females. When pregnant, however, females can weigh as much as 500 kg (1,102 lb). The polar bear is among the most sexually dimorphic of mammals, surpassed only by the pinnipeds such as elephant seals. The largest polar bear on record, reportedly weighing 1,002 kg (2,209 lb), was a male shot at Kotzebue Sound in northwestern Alaska in 1960. This specimen, when mounted, stood 3.39 m (11 ft 1 in) tall on its hindlegs. The shoulder height of an adult polar bear is 122 to 160 cm (4 ft 0 in to 5 ft 3 in). While all bears are short-tailed, the polar bear’s tail is relatively the shortest amongst living bears, ranging from 7 to 13 cm (2.8 to 5.1 in) in length.

Compared with its closest relative, the brown bear, the polar bear has a more elongated body build and a longer skull and nose. As predicted by Allen’s rule for a northerly animal, the legs are stocky and the ears and tail are small. However, the feet are very large to distribute load when walking on snow or thin ice and to provide propulsion when swimming; they may measure 30 cm (12 in) across in an adult. The pads of the paws are covered with small, soft papillae (dermal bumps), which provide traction on the ice. The polar bear’s claws are short and stocky compared to those of the brown bear, perhaps to serve the former’s need to grip heavy prey and ice. The claws are deeply scooped on the underside to assist in digging in the ice of the natural habitat. Research of injury patterns in polar bear forelimbs found injuries to the right forelimb to be more frequent than those to the left, suggesting, perhaps, right-handedness. Unlike the brown bear, polar bears in captivity are rarely overweight or particularly large, possibly as a reaction to the warm conditions of most zoos.

The 42 teeth of a polar bear reflect its highly carnivorous diet. The cheek teeth are smaller and more jagged than in the brown bear, and the canines are larger and sharper. The dental formula is $ \frac{3.1.4.2}{3.1.4.3} $

Polar bears are superbly insulated by up to 10 cm (4 in) of adipose tissue, their hide and their fur; they overheat at temperatures above 10 °C (50 °F), and are nearly invisible under infrared photography. Polar bear fur consists of a layer of dense underfur and an outer layer of guard hairs, which appear white to tan but are actually transparent. The guard hair is 5–15 cm (2–6 in) over most of the body. Polar bears gradually moult from May to August, but, unlike other Arctic mammals, they do not shed their coat for a darker shade to camouflage themselves in the summer conditions. The hollow guard hairs of a polar bear coat were once thought to act as fiber-optic tubes to conduct light to its black skin, where it could be absorbed; however, this hypothesis was disproved by a study in 1998.

The white coat usually yellows with age. When kept in captivity in warm, humid conditions, the fur may turn a pale shade of green due to algae growing inside the guard hairs. Males have significantly longer hairs on their forelegs, which increase in length until the bear reaches 14 years of age. The male’s ornamental foreleg hair is thought to attract females, serving a similar function to the lion’s mane.

The polar bear has an extremely well developed sense of smell, being able to detect seals nearly 1.6 km (1 mi) away and buried under 1 m (3 ft) of snow. Its hearing is about as acute as that of a human, and its vision is also good at long distances.

The polar bear is an excellent swimmer and often will swim for days. One bear swam continuously for 9 days in the frigid Bering Sea for 400 mi (687 km) to reach ice far from land. She then travelled another 1,100 mi (1,800 km). During the swim, the bear lost 22% of her body mass and her yearling cub died. With its body fat providing buoyancy, the bear swims in a dog paddle fashion using its large forepaws for propulsion. Polar bears can swim 10 km/h (6 mph). When walking, the polar bear tends to have a lumbering gait and maintains an average speed of around 5.6 km/h (3.5 mph). When sprinting, they can reach up to 40 km/h (25 mph).

Hunting and diet

The polar bear is the most carnivorous member of the bear family, and throughout most of its range, its diet primarily consists of ringed (Pusa hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). The Arctic is home to millions of seals, which become prey when they surface in holes in the ice in order to breathe, or when they haul out on the ice to rest. Polar bears hunt primarily at the interface between ice, water, and air; they only rarely catch seals on land or in open water.

The polar bear’s most common hunting method is called still-hunting: The bear uses its excellent sense of smell to locate a seal breathing hole, and crouches nearby in silence for a seal to appear. The bear may lay in wait for several hours. When the seal exhales, the bear smells its breath, reaches into the hole with a forepaw, and drags it out onto the ice. The polar bear kills the seal by biting its head to crush its skull. The polar bear also hunts by stalking seals resting on the ice: Upon spotting a seal, it walks to within 90 m (100 yd), and then crouches. If the seal does not notice, the bear creeps to within 9 to 12 m (30 to 40 ft) of the seal and then suddenly rushes forth to attack. A third hunting method is to raid the birth lairs that female seals create in the snow.

A widespread legend tells that polar bears cover their black noses with their paws when hunting. This behaviour, if it happens, is rare – although the story exists in the oral history of northern peoples and in accounts by early Arctic explorers, there is no record of an eyewitness account of the behaviour in recent decades.

Mature bears tend to eat only the calorie-rich skin and blubber of the seal, which are highly digestible, whereas younger bears consume the protein-rich red meat. Studies have also photographed polar bears scaling near-vertical cliffs, to eat birds’ chicks and eggs. For subadult bears, which are independent of their mother but have not yet gained enough experience and body size to successfully hunt seals, scavenging the carcasses from other bears’ kills is an important source of nutrition. Subadults may also be forced to accept a half-eaten carcass if they kill a seal but cannot defend it from larger polar bears. After feeding, polar bears wash themselves with water or snow.

Although polar bears are extraordinarily powerful, its primary prey species, the ringed seal, is much smaller than itself, and many of the seals hunted are pups rather than adults. Ringed seals are born weighing 5.4 kg (12 lb) and grown to an estimated average weight of only 60 kg (130 lb). They also in places prey heavily upon the harp seal (Pusa groenlandica) or the harbor seal. The bearded seal, on the other hand, can be nearly the same size as the bear itself, averaging 270 kg (600 lb). Adult male bearded seals, at 350 to 500 kg (770 to 1,100 lb) are too large for a female bear to overtake, and so are potential prey only for mature male bears. Large males also occasionally attempt to hunt and kill even larger prey items. It can kill an adult walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), although this is rarely attempted. At up to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) and a typical adult mass range of 600 to 1,500 kg (1,300 to 3,300 lb), a walrus can be more than twice the bear’s weight, and has up to 1-metre (3 ft)-long ivory tusks that can be used as formidable weapons. A polar bear may charge a group of walruses, with the goal of separating a young, infirm, or injured walrus from the pod. They will even attack adult walruses when their diving holes have frozen over or intercept them before they can get back to the diving hole in the ice. Yet, polar bears will very seldom attack full-grown adult walruses, with the largest male walrus probably invulnerable unless otherwise injured or incapacitated. Since an attack on a walrus tends to be an extremely protracted and exhausting venture, bears have been known to back down from the attack after making the initial injury to the walrus. Polar bears have also been seen to prey on beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros), by swiping at them at breathing holes. The whales are of similar size to the walrus and nearly as difficult for the bear to subdue. Most terrestrial animals in the Arctic can outrun the polar bear on land as polar bears overheat quickly, and most marine animals the bear encounters can outswim it. In some areas, the polar bear’s diet is supplemented by walrus calves and by the carcasses of dead adult walruses or whales, whose blubber is readily devoured even when rotten. Polar bears sometimes like to go fishing where they swim underwater to catch fish like the Arctic charr or the fourhorn sculpin.

With the exception of pregnant females, polar bears are active year-round, although they have a vestigial hibernation induction trigger in their blood. Unlike brown and black bears, polar bears are capable of fasting for up to several months during late summer and early fall, when they cannot hunt for seals because the sea is unfrozen. When sea ice is unavailable during summer and early autumn, some populations live off fat reserves for months at a time, as polar bears do not ‘hibernate’ any time of the year.

Being both curious animals and scavengers, polar bears investigate and consume garbage where they come into contact with humans. Polar bears may attempt to consume almost anything they can find, including hazardous substances such as styrofoam, plastic, car batteries, ethylene glycol, hydraulic fluid, and motor oil. The dump in Churchill, Manitoba was closed in 2006 to protect bears, and waste is now recycled or transported to Thompson, Manitoba.

Dietary flexibility

Although seal predation is the primary and an indispensable way of life for most polar bears, when alternatives are present they are quite flexible. Polar bears will consume a wide variety of other wild foods, including muskox (Ovibos moschatus), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), birds, eggs, rodents, crabs, other crustaceans and other polar bears. They may also eat plants, including berries, roots, and kelp, however none of these are a significant part of their diet, except that beachcast marine mammal carcasses are an exception. When stalking land animals, such as muskox, reindeer, and even willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus), polar bears appear to make use of vegetative cover and wind direction to bring them as close to their prey as possible before attacking. Polar bears have been observed to hunt the small Svalbard reindeer (R. t. platyrhynchus), which weigh only 40 to 60 kg (90 to 130 lb) as adults, as well as the barren-ground caribou (R. t. groenlandicus), which is about twice as heavy as that. Adult muskox, which can weigh 450 kg (1,000 lb) or more, are a more formidable quarry. Although ungulates are not typical prey, the killing of one during the summer months can greatly increase the odds of survival during that lean period. Like the brown bear, most ungulate prey of polar bears is likely to be young, sickly or injured specimens rather than healthy adults. The polar bear’s biology is specialized to require large amounts of fat from marine mammals, and it cannot derive sufficient caloric intake from terrestrial food.

In their southern range, especially near Hudson Bay and James Bay, Canadian polar bears endure all summer without sea ice to hunt from. Here, their food ecology shows their dietary flexibility. They still manage to consume some seals, but they are food-deprived in summer as only marine mammal carcasses are an important alternative without sea ice, especially carcasses of the beluga whale. These alternatives may reduce the rate of weight loss of bears when on land. One scientist found that 71% of the Hudson Bay bears had fed on seaweed (marine algae) and that about half were feeding on birds like sea ducks, especially the oldsquaw (53%), common eider, long-tailed duck or dovekie by swimming underwater to catch them. They were also diving to feed on blue mussels and other underwater food sources like the green sea urchin. 24% had eaten moss recently, 19% had consumed grass, 34% had eaten black crowberry and about half had consumed willows. This study illustrates the polar bear’s dietary flexibility but it does not represent its life history elsewhere. Most polar bears elsewhere will never have access to these alternatives, except for the marine mammal carcasses that are important wherever they occur.

In Svalbard, polar bears were observed to kill white-beaked dolphins during spring, when the dolphins were trapped in the sea ice. The bears then proceeded to cache the carcasses, which remained and were eaten during the ice-free summer and autumn.

author