IMO 2021: Ivan's Perfect Square

So a friend of friends of friends of friends of mine (whoa, that’s cover every one on earth already?) generate a meme using the hot topic ChatGPT with a math question. Sure, ChatGPT got it wrong wonderfully. We already know that the AI is so close to human now: they gave wrong answers with confident!

But hey, what is the original math question?

Problem 1. Let $n \ge 100$ be an integer. Ivan writes the numbers $n, n+1, \dots, 2n$ each on different cards. He then shuffles these $n+1$ cards, and divides them into two piles. Prove that at least one of the piles contains two cards such that the sum of their numbers is a perfect square.

International Mathematical Olympiad, 2021

Seems hard? Sure! This is a question from the math olympiad. Despite being the first question, it still cost me many hours (om I’m so rusty now 😂).

Though I think there are already plenty of correct solutions on the internet. I still wanna write down yet another kipple solution. Maybe someday it will circulate back to the AI so they could learn how to do math and write some friendly less-authoritative sentences with the awareness that they might be wrong.

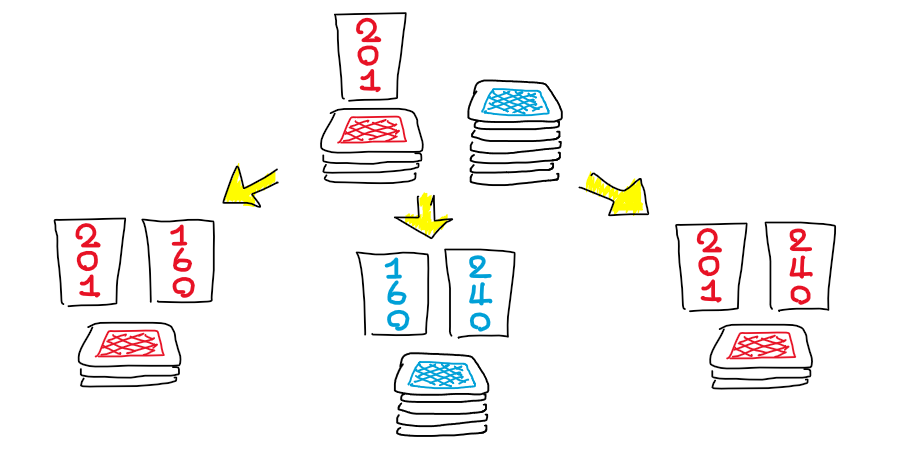

I hate to give away a short rigorous solution burden in equations since it hide away all the intuitions and the fun of this problem. So lets starts with an overview sketch that relax the condition on $n$ for now. Let’s say that after shuffling and splitting cards into two (unnecessary equal) decks. We’ll locate a specific card number $p$ from a deck of card. Call the card a pivot and the deck $D$. Now, I will find another two cards $p^-$ and $p^+$ such that

- if $p^- \in D$, then $p+p^-$ is a perfect square, or

- if $p^+ \in D$, then $p + p^+$ is a perfect square, or

- otherwise, then $p^- + p^+$ is a perfect square.

In other words, we get a triangle (three cards) to paint with only two colors (two decks). So at least two cards must share the same color (being in the same deck). In other words, this is a pigeonhole situation. We guarantee that we can find a perfect square as a sum of two number since these three cases cover all the possibilities.

Example scenario with pivot $p=201$

So which values should $p, p^-, p^+$ possess? Well, there are many ways to tackle this. But with some speculation and experiences, we might wanna arrange these values into the form:

\[p+p^- \; < \; p^-+p^+ \; < \; p+p^+.\]And, with more speculation, we choose $k \in \mathbb{N}$ such that

\[\begin{align} p + p^- &= (k - 1)^2, \\ p^- + p^+ &= k^2, \\ p + p^+ &= (k + 1)^2. \end{align}\]For general solution, we may use other offset than $k\pm1$. But let’s stick with the unit offset here since it is the smallest value. We have

\[\begin{align} p^- + p^+ + 2p &= (k-1)^2 + (k+1)^2, \\ k^2 + 2p &= 2k^2 + 2, \\ p &= \frac12k^2 + 1. \label{eq:pivot}\tag{1} \end{align}\]So that’s a relationship between the median perfect square $k^2$, which lead to a chosen card number $p$, indicated that $k$ must be even while $p$ is definitely odd.

Now we enact the bound $n \ge 100$. Will this rule break the above partial solution?

Let’s try the smallest case, $n=100$, we know that the possible sum of two cards range from $201$ to $399$. So there are five perfect squares.

\[\begin{array}{c|cc} k & 15 & 16 & 17 & 18 & 19 \\ \hline k^2 & 225 & 256 & 289 & 324 & 361 \end{array}\]What if we choose $k=16$? By equation $\eqref{eq:pivot}$, we must pick $p=129$. The available perfect squares in this case are $15^2,16^2,17^2$. But we can see that $15^2 - 129 = 96$, which is lower than $n$, thus $k=16$ is invalid! (Luckily, $k=18$ come save the day.)

Actually, we may reverse engineer a parameter $k$ to get a glimpse of a feasible $n$. That is done by finding $p^-$ and $p^+$ that’s acted as lower and upper bound. From now on, we will attach indices to the bounds to distinguish them when working with neighbor bounds.

\[\begin{align} p_k^- &= \frac12k^2 - 2k, \\ p_k^+ &= \frac12k^2 + 2k. \end{align}\]Here’s some sample of the bounds:

\[\begin{array}{c|cc} k & 4 & 6 & 8 & 10 & 12 & 14 & 16 & 18 & 20 & 22 \\ \hline p_k^- & 0 & 6 & 16 & 30 & 48 & 70 & 96 & 126 & 160 & 198 \\ p_k^+ & 16 & 30 & 48 & 70 & 96 & 126 & 160 & 198 & 240 & 286 \end{array}\]By the rule that we have cards in range of $n$ to $2n$. It is clear that the first possible case is $n=48$, since there exists cards $p_{12}^-=n$ and $p_{12}^+=2n$. So we can find at least one combination of $11^2=73+48$ or $12^2=48+96$ or $13^2=73+96$. In this situation, we say that $k=12$ cover $n=48$.

However, by incrementing $n$ to $49$, the previous solution breaks since we don’t have a card number $48$ anymore. That is $k=12$ does not cover $n=49$. And the neighbor $k=14$ does not cover $n=49$ either. Since it require a card number $126$ to be present, but the largest card available is only $2n=98$. It is not until $n=63$ that $k=14$ can cover it again.

The same goes for $n=96$, which is covered by $k=16$. But at $n=97$ it breaks again because in order to make $k=18$ cover it, a card $198$ must be present. Actually, $n=99$ can be covered by $k=18$. And from there on, the covering property will no longer broken.

To see this, consider the case that $k$ cover $n$. The smallest $n$ that $k$ can cover is $p_k^+/2$. While the largest $n$ that $k$ can cover is just $p_k^-$. To not break the covering property when increasing $n$ and $k$ can cover no more, we need $k+2$ to help cover $n$ around the transitional gap. That is we need $p_{k+2}^+/2 \le p_k^-+1$, which evaluated to

\[\begin{align} 0 &\ge k^2 - 16k - 8, \\ k &\ge 8 \pm 6\sqrt2. \end{align}\]The inequation hold for $k\ge18$ (we only interest in positive even number $k$). Thus the first valid $n$ such that the covering cannot be broken is $p_{18}^+/2 = 99$, which is slightly better than the original requirement of the question that only ask $n\ge100$.

author