Hypersphere & resizing determinant dimension

Consider a sphere in $n$ dimension (an $(n{-}1)$-sphere) with an unknown focus and radius. However, if we randomly choose $n{+}1$ points on its boundary, we can deduce this information. The system of equations for this calculation is:

\[(a_{k1}-x_1)^2 + (a_{k2}-x_2)^2 + \cdots + (a_{kn}-x_n)^2 = r^2. \tag{1} \label{eq:sphere}\]When points on the boundary are denoted as $p_k = (a_{k1},a_{k2},\dots,a_{kn})$ for $0\le k\le n$, we can determine the focus at $f=(x_1,x_2,\dots,x_n)$ and the radius of length $r$.

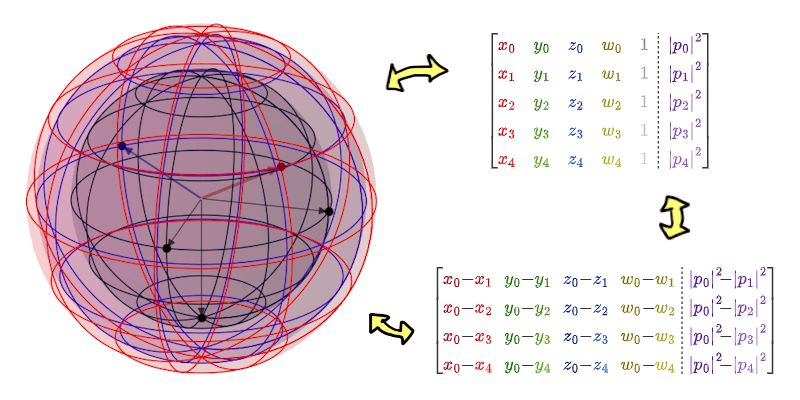

Example of 4D hypersphere, and two ways to interpreting the data points.

Of course we want to solve the system of equations $\eqref{eq:sphere}$ for the focus and radius. But we cannot work well with it, yet, since each $x_i$ is coupled with data raised to a power of two. If we expand these equations, we obtain

\[\begin{align} (a_{k1}^2 - 2a_{k1}x_1 + x_1^2) + \cdots + (a_{kn}^2 - 2a_{kn}x_n + x_n^2) &= \\ (a_{k1}^2 + \cdots + a_{kn}^2) - 2(a_{k1}x_1 + \cdots + a_{kn}x_n) + (x_1 + \cdots + x_n)^2 &= \\ \abs{p_k}^2 - 2(a_{k1}x_1 + \cdots + a_{kn}x_n) + \abs{f}^2 &= r^2. \end{align}\]In other words,

\[2a_{k1}x_1 + 2a_{k2}x_2 + \cdots + 2a_{kn}x_n + (r^2{-}\abs{f}^2) = \abs{p_k}^2. \tag{2} \label{eq:row}\]That means we can treat the term $(r^2{-}\abs{f}^2)$ as a single variable. This transformation turns $\eqref{eq:row}$ into a system of linear equations with $n+1$ variables! Which yield us a matrix

\[\begin{bmatrix} a_{01} & a_{02} & \cdots & a_{0n} & 1 \\ a_{11} & a_{12} & & a_{1n} & 1 \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ a_{n1} & a_{n2} & \cdots & a_{nn} & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2x_1 \\ \vdots \\ 2x_n \\ r^2{-}\abs{f}^2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \abs{p_0}^2 \\ \abs{p_1}^2 \\ \vdots \\ \abs{p_n}^2 \end{bmatrix}.\]Next, we apply Cramer’s rule to determine the coordinates,

\[2x_i = \frac{ \det\begin{bmatrix} a_{01} & \cdots & a_{0,i-1} & \abs{p_0}^2 & a_{0,i+1} & \cdots & a_{0n} & 1 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ a_{n1} & \cdots & a_{n,i-1} & \abs{p_n}^2 & a_{n,i+1} & \cdots & a_{nn} & 1 \end{bmatrix} }{ \det\begin{bmatrix} a_{01} & \cdots & a_{0n} & 1 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ a_{n1} & \cdots & a_{nn} & 1 \end{bmatrix} }. \tag{3} \label{eq:full-det}\]The same approach applies to the radius, only that we have to change the last column vector from $\vec{1}$ to $[\abs{p_1}^2,\dots,\abs{p_n}^2]$ instead.

This method is ok, for the most part. However, I sense a slight inconsistency when calculating for $r$. For instance, we must solve for all $x_i$ first (so we have $\abs{f}^2$). Additionally, the determinant pattern for solving $r$ is not quite similar to that for other $x_i$. Moreover, in practice, we don’t necessarily need the determinant; Pythagorean theorem is often more than enough.

Thus, we may reframe this problem to focus solely on finding the focus (no pun intended). That involves reducing the problem to a system of equations of $n$ variables. It’s worth noting that each equation in $\eqref{eq:row}$ contains the exact same variable $(r^2{-}\abs{f}^2)$. To solve this, we can use the equation with $p_0$ as the minuend and substract the remaining equations, resulting in

\[2(a_{01}{-}a_{k1})x_1 + 2(a_{02}{-}a_{k2})x_2 + \cdots + 2(a_{0n}{-}a_{kn})x_n = \abs{p_0}^2{-}\abs{p_k}^2.\]Or, in matrix form:

\[\begin{bmatrix} a_{01}{-}a_{11} & a_{02}{-}a_{12} & \cdots & a_{0n}{-}a_{1n} \\ a_{01}{-}a_{21} & a_{02}{-}a_{22} & & a_{0n}{-}a_{2n} \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{01}{-}a_{n1} & a_{02}{-}a_{n2} & \cdots & a_{0n}{-}a_{nn} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2x_1 \\ 2x_2 \\ \vdots \\ 2x_n \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \abs{p_0}^2{-}\abs{p_1}^2 \\ \abs{p_0}^2{-}\abs{p_2}^2 \\ \vdots \\ \abs{p_0}^2{-}\abs{p_n}^2 \end{bmatrix}.\]Result in the answer

\[2x_i = \frac{ \det\begin{bmatrix} a_{01}{-}a_{11} & \cdots & a_{0,i-1}{-}a_{1,i-1} & \abs{p_0}^2{-}\abs{p_1}^2 & a_{0,i+1}{-}a_{1,i+1} & \cdots & a_{0n}{-}a_{1n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{01}{-}a_{n1} & \cdots & a_{0,i-1}{-}a_{n,i-1} & \abs{p_0}^2{-}\abs{p_n}^2 & a_{0,i+1}{-}a_{n,i+1} & \cdots & a_{0n}{-}a_{nn} \\ \end{bmatrix} }{ \det\begin{bmatrix} a_{01}{-}a_{11} & \cdots & a_{0n}{-}a_{1n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{01}{-}a_{n1} & \cdots & a_{0n}{-}a_{nn} \\ \end{bmatrix} }. \tag{4} \label{eq:sub-det}\]Although equation $\eqref{eq:full-det}$ and $\eqref{eq:sub-det}$ differ in detail, they yield the same answer. Besides, they share an overall similar structure, particularly in the denominator’s determinant. We may guess that these denominators are equal, or at least share the same multiplier with their numerators, such as $-1$. This leads us to formulate a conjecture.

Conjecture 1: Given vector $\color{red}\vec{u}$ and matrix $M=[\vec{v}_1,\cdots,\vec{v}_n]$, we propose

\[\det\left[\begin{array}{cccc:c} \color{red}u_1 & \color{red}u_2 & \color{red}\cdots & \color{red}u_n & 1 \\ \hdashline v_{11} & v_{12} & \cdots & v_{1n} & 1 \\ v_{21} & v_{22} & & v_{2n} & 1 \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ v_{n1} & v_{n2} & \cdots & v_{nn} & 1 \end{array}\right] = \det\begin{bmatrix} {\color{red}u_1}{-}v_{11} & {\color{red}u_2}{-}v_{12} & \cdots & {\color{red}u_n}{-}v_{1n} \\ {\color{red}u_1}{-}v_{21} & {\color{red}u_2}{-}v_{22} & & {\color{red}u_n}{-}v_{2n} \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots \\ {\color{red}u_1}{-}v_{n1} & {\color{red}u_2}{-}v_{n2} & \cdots & {\color{red}u_n}{-}v_{nn} \\ \end{bmatrix}.\]It is rather complicated to prove the above conjecture. Therefore, we should revisit some properties of determinants.

Property 2: For convenient, let $M(k:\vec{u})$ denote the action of overwriting column $k$ of matrix $M$ with column vector $\vec{u}$ (similarly, let $M(k:c) = M(k:c{\cdot}\vec{1})$ when $c$ is a scalar).

- Factor out a multiplier from one column: $r{\cdot}\det M = \det M(k:r{\cdot}\vec{v}_k)$, for any real number $r$.

- Expand column addition: $\det M(k:\vec{u}{+}\vec{w}) = \det M(k:\vec{u}) + \det M(k:\vec{w})$.

- Determinant is zero when two columns are identical: $\det M(i: \vec{u}, j: \vec{u}) = 0$.

- Determinant is negative when two columns are swapped: $\det M = -\det M(i:\vec{v}_j,j:\vec{v}_i)$.

Lemma 3: $\det M + \det M(k:c) = \det M(k:\vec{v}_k{+}c)$.

Lemma 4: $\det M + \det M(i:c_i) + \det M(j:c_j) = \det M(i:\vec{v}_i{+}c_i,j:\vec{v}_j{+}c_j)$.

Proof First, observe that from Property 2.1 and 2.3, we have

\[\det M(i:c_i,j:c_j) = c_ic_j \det M(i:\vec{1},j:\vec{1}) = 0.\]Thus,

\[\begin{align} &\det M + \det M(i:c_i) + \det M(j:c_j) \\ &\qquad= \det M(i:\vec{v}_i{+}c_i) + \det M(j:c_j) \\ &\qquad= \det M(i:\vec{v}_i{+}c_i) + \det M(j:c_j) + \det M(i:c_i,j:c_j) \\ &\qquad= \det M(i:\vec{v}_i{+}c_i) + \det M(i:\vec{v}_i{+}c_i,j:c_j) \\ &\qquad= \det M(i:\vec{v}_i{+}c_i,j:\vec{v}_j{+}c_j). \tag*{$\blacksquare$} \end{align}\]Corollary 5: $\det M + \sum_{k\in K}\det M(k:c_k) = \det M(i:\vec{v}_k{+}c_k \mid k\in K)$, for any index set $K$.

We are now ready to prove Conjecture 1.

Proof (of Conjecture 1) From Laplace expansion, we can express a determinant as a series of determinants with one smaller dimension

\[\det\left[\begin{array}{cccc:c} \color{red}u_1 & \color{red}u_2 & \color{red}\cdots & \color{red}u_n & \color{blue}1 \\ \hdashline v_{11} & v_{12} & \cdots & v_{1n} & 1 \\ v_{21} & v_{22} & & v_{2n} & 1 \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ v_{n1} & v_{n2} & \cdots & v_{nn} & 1 \end{array}\right] = {\color{red}u_1} \det\begin{bmatrix} v_{12} & \cdots & v_{1n} & 1 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ v_{n2} & \cdots & v_{nn} & 1 \end{bmatrix} - \cdots \pm {\color{blue}1} \det\begin{bmatrix} v_{11} & \cdots & v_{1n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ v_{n1} & \cdots & v_{nn} \end{bmatrix}.\]Notice that each term (except the last) always contains a column vector $\vec{1}$. We will swap this column with the column that was $\vec{v}_k$ before the minor expansion. Each term requires a different number of swaps. For example, the second-to-last term requires no swaps, while the first term requires $n{-}1$ swaps. After swapping, we reduce the sum into a single determinant (using Corollary 5). That is

\[\begin{align} \det\left[\begin{array}{c:c} \color{red}\vec{u} & 1 \\ \hdashline M & \vec{1} \end{array}\right] &= (-1)^{n-1} {\color{red}u_1}\det M(1:\vec{1}) + \cdots + (-1)^{n-1} {\color{red}u_n}\det M(n:\vec{1}) + (-1)^n \det M \\ &= (-1)^n \Big( \det M(1:{\color{red}-u_1}) + \cdots + \det M(n:{\color{red}-u_n}) + \det M \Big) \\ &= (-1)^n \det M(k:\vec{v}_k{\color{red}-u_k} \mid k \in \lbrace 1,\cdots,n \rbrace) \\ &= (-1)^n \det\begin{bmatrix} v_{11}{\color{red}-u_1} & v_{12}{\color{red}-u_2} & \cdots & v_{1n}{\color{red}-u_n} \\ v_{21}{\color{red}-u_1} & v_{22}{\color{red}-u_2} & & v_{2n}{\color{red}-u_n} \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots \\ v_{n1}{\color{red}-u_1} & v_{n2}{\color{red}-u_2} & \cdots & v_{nn}{\color{red}-u_n} \end{bmatrix}. \end{align}\]Observe that every column in this matrix is $\vec{v}_{k}{\color{red}-u_k}$, but our conjecture needs it to be ${\color{red}u_k}{-}\vec{v}_k$. This can be resolved by expanding $(-1)^n$ back into the matrix. Q.E.D.

author