Movement, group, and torus

Imagine that you’re a pixel on a 2D screen with the ability to move to adjacent pixels in 4 directions: left, right, up, and down. Your character can receive multiple movement commands simultaneously, and you’ll see the accumulated result as one big move (think of it as pressing D-pad diagonally). It is easy to see that you can move to any pixel on the screen, given that there’s no obstacles (and, for simplicity, we’ll considered there’s no obstacles for this entire post).

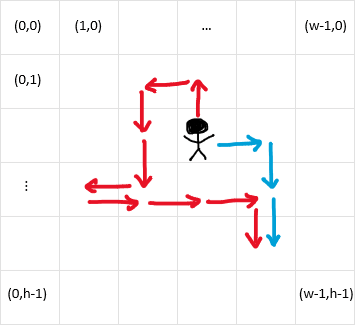

Coordinate system and example sequence of movements

If we encoded positions as $(x,y)$ coordinates, starting at $(0,0)$ in the top-left corner1, we can describe movements like this:

move (x,y) [] = (x,y)

move (x,y) ('L':ms) = move (x-1,y) ms

move (x,y) ('R':ms) = move (x+1,y) ms

move (x,y) ('U':ms) = move (x,y-1) ms

move (x,y) ('D':ms) = move (x,y+1) ms

For example, the command:

move (6,6) "ULDDLRRRD"

instructs us to move up, then left, down twice, left again, but then change our mind and move right three times, and finally move down once more. We end up at $(7,8)$, given that we start at $(6,6)$.

It’s easy to notice that some movements cancel each other out, i.e., a pair of L and R, and a pair of U and D. So, the command above could be shortened to:

move (6,6) "ULDDRRD"

Working with this coding-style command might make it tricky to spot such simplification, but we can model it differently! Instead, let’s use vectors to encode the coordinates.2 Hence, the command is equivalent to

\[\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}0\\-1\end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix} + 2\begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix} + 3\begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}x{+}1\\y{+}2\end{bmatrix}.\]We can see that the equation can reduce the lengthiness command even more, cancelling out far-apart pairs.

Why does this work? In short, because $(\mathbb{Z}^2,+)$ is a group (more precisely, an abelian group).

But what is a group?

A group is a mathematical structure where elements behave nicely together. Each element interacts with one another through a binary operator. Here, each vector $(x,y) \in \mathbb{Z}^2$ is an element of the group, and vector addition ($+$) is the binary operator. The basic requirement is that whenever we take two elements and apply the operator, the result is always still part of the group.

The rules that govern the group are:

- Associativity: When more than two elements interacting with each other, the order of parenthesis doesn’t matter. In other words, $(\vec{v}+\vec{u})+\vec{w}=\vec{v}+(\vec{u}+\vec{w})$.

- Identity: The group has exactly one element $e$ that does nothing when interacting with others. In this case $e=(0,0)$, because $\vec{v}+e=\vec{v}$.

- Inverse: Every element $\vec{v}$ has an inverse that brings it back to the identity. So, $\vec{v} +(- \vec{v}) = (0,0)$, which means $-\vec{v}$ is the inverse of $\vec{v}$, and vice versa.

These 3 rules are the core properties that constitute a group. What’s special for this group is it also has another additional rule (no pun intended!)

- Commutativity: The order of elements also doesn’t matter, $\vec{v}+\vec{u} = \vec{u}+\vec{v}$.

Groups that obey the 4th rule are called abelian groups, although we won’t focus on this too much.3 What’s important is the 1st rule where parenthesis doesn’t matter (which, in turn, makes us lazy mathematicians write equations parenthesesless whenever possible).

Thus, with all 4 rules enact, our pixel-character has a well-regulated set of movements with neat mathematical properties, making simplification simple.

So far so good… right?

Out-of-bound issue

Here’s the catch: $(\mathbb{Z}^2,+)$ is kinda useless in the real world, because it doesn’t care if our character is still visible on the screen.4 For example, what if your cat jumps onto your keyboard and sends your character flying off the edge? How do we get them back?

We may prevent such out-of-bound movements by stopping the character from moving past the screen boundaries. Think of it as having an invisible wall surround the screen.

(w,h) = (80,24)

move' (x,y) [] = (x,y)

move' (x,y) ('L':ms) = move' (x',y) ms where x' = max 0 (x-1)

move' (x,y) ('R':ms) = move' (x',y) ms where x' = min (w-1) (x+1)

move' (x,y) ('U':ms) = move' (x,y') ms where y' = max 0 (y-1)

move' (x,y) ('D':ms) = move' (x,y') ms where y' = min (h-1) (y+1)

Or, expressing via a mathematics operator $\boxplus$,

\[\begin{bmatrix}x_1\\y_1\end{bmatrix} \boxplus \begin{bmatrix}x_2\\y_2\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\min(\max(x_1{+}x_2,0),w{-}1)\\\min(\max(y_1{+}y_2,0),h{-}1)\end{bmatrix}.\]The sad thing is $\boxplus$ breaks associativity. Take a counter-example:

\[\begin{bmatrix}1\\42\end{bmatrix} = \left( \begin{bmatrix}0\\42\end{bmatrix} \boxplus \begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix} \right) \boxplus \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} \quad\ne\quad \begin{bmatrix}0\\42\end{bmatrix} \boxplus \left( \begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix} \boxplus \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} \right) = \begin{bmatrix}0\\42\end{bmatrix}.\]Thus, we cannot simplify the sequence of movements into just one vector anymore. Instead, we have to execute each movement step-by-step in the received order.

In other words, $(\mathbb{Z}^2,\boxplus)$ is no longer a group.

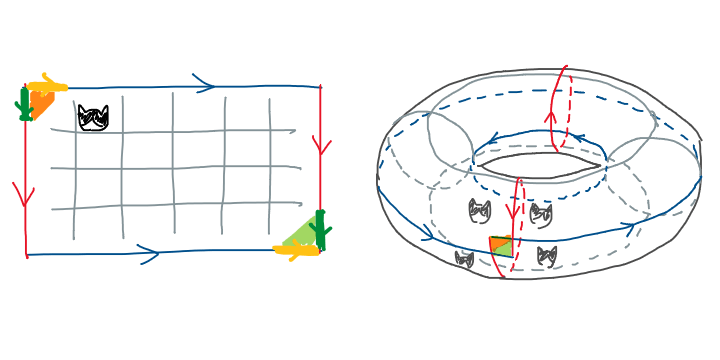

Asteroid is on a torus

As we’ve seen, clamping mechanic might not be an ideal way to move our pixel-character (it sure has many important real-world applications, but that’s a story for another time). So, are there other designs that preserved these mathematical properties?

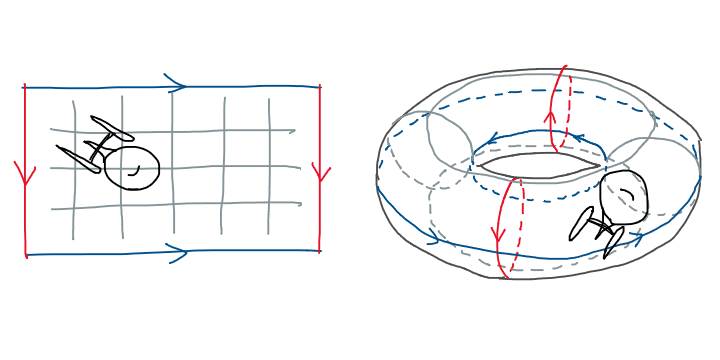

Now, if you’re like me, a gamer who’s into classic games, you might recall the iconic Asteroids (1979). You’re a spaceship dodging and blasting– you guess it right that’s the name of the game –asteroids. The notable mechanic in the game is that when the spaceship (and also asteroids) flies off the left edge of the screen, it magically reappears on the right edge (and vice versa).

The mechanic is specifically known among gamers as wraparound. It’s not that mind-blowing mechanic, but a natural consequence when we try to project the Earth onto a rectangle. Take a look at Mercator map, one who’s not a flat earther will draw a conclusion that if you keep heading west pass Hawaii, you’ll loop back to visit Japan from the east.

What makes Asteroids special, though, is that it doesn’t just wrap horizontally, but also vertically. That’s made Asteroid’s universe a torus!5

Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, points to the possibility that our universe possesses the shape of a torus.

Well, implementing this torus-style movement is a lot simpler,

(w,h) = (80,24)

move'' (x,y) [] = (x,y)

move'' (x,y) ('L':ms) = move'' (x',y) ms where x' = (x-1) `mod` w

move'' (x,y) ('R':ms) = move'' (x',y) ms where x' = (x+1) `mod` w

move'' (x,y) ('U':ms) = move'' (x,y') ms where y' = (y-1) `mod` h

move'' (x,y) ('D':ms) = move'' (x,y') ms where y' = (y+1) `mod` h

Mathematically,

\[\begin{bmatrix}x_1\\y_1\end{bmatrix} \oplus \begin{bmatrix}x_2\\y_2\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}x_1+x_2\pmod{w}\\y_1+y_2\pmod{h}\end{bmatrix}.\]With the mightiness of $\oplus$, elements are crumble down into a finite set, for convenience,

\[\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)} = (\mathbb{Z}/w\mathbb{Z}) \times (\mathbb{Z}/h\mathbb{Z}).\]Note that $\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z}$ is just a fancy way of writing a set of integers modulo $n$, that is $\lbrace0,1,2,\dots,n{-}1\rbrace$.

It’s straightforward to show that the set is closed under $\oplus$. And we can quickly verify that the above 3(+1) group rules still hold. Thus, $(\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)},\oplus)$ is indeed a group.

Generating a group

We designed $(\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)},\oplus)$ with a real-world concept of moving our pixel-character in 4 directions. But since we’re now working in modular arithmetic, we’ll soon discover that some moves are actually redundant. For example, instead of moving left by 1 step, we could move right by $w{-}1$ steps.

Of course, that’s an inefficient way to move, but theoretically, it reveals a key foundation of the group: we can safely ditch the “move-left” command, and everything is still intact. The same applies to the pair of up-down movement. The reason is simple: those movements are just an inverse of one another.

So, we can starts with a subset $S \subset \mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)}$ as small as

\[S = \left\lbrace \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} \right\rbrace.\]It’s easy to see that combining the elements in $S$ under the operation $\oplus$ for a finite number of times allows us to reach every element in the set. Thus, we say that $S$ is a set of generators of $\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)}$.6

Can we have different generators? Absolutely! And there are many of them. One instance would be: instead of moving one pixel at a time horizontally (on a screen of width $w=80$), we may jump by 3 pixels instead. That means $S = \lbrace (3,0), (0,1) \rbrace$ is another generators set. Just be careful: jumping 3 pixels vertically (on a screen of height $h=24$) does not work because $\gcd(3,24) \ne 1$.

Another naturally interesting question is: can we have an even smaller set of generators (like, $\abs{S}=1$)? Too bad the answer is no, since the operator $\oplus$ separates the plane into two independent axes. But what if we alter the operator $\oplus$ yet again…

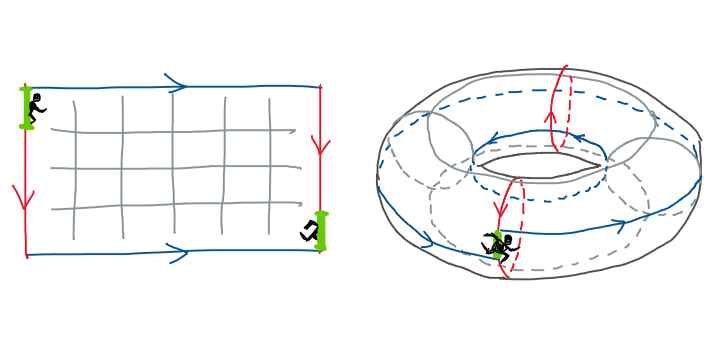

Typewriter is on a twisted torus

Let’s consider an operator $\hat\oplus$, with a unique twist:

\[\begin{bmatrix}x_1\\y_1\end{bmatrix} \:\hat\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}x_2\\y_2\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1+x_2\pmod{w} \\ x_q+y_1+y_2\pmod{h} \end{bmatrix},\]where

\[x_q = \left\lfloor\frac{x_1+x_2}{w}\right\rfloor.\]The definition seems intimidating at first glance. But, in Layman’s term, it just says: when moving right off the screen one time, wraparound to the left and also move down one step, however, moving down off the screen to the bottom wraparound to the top without affecting horizontal movement.

The portal is a lie.

Now the operator look a lot more familiar. Indeed, our beloved text processors, even tracking back to typewriters, are the perfect example! As we type left-to-right, and top-to-bottom, when we reach the end of a line, jump the cursor to the beginning of the next line. When we reach the end of a page, well, loop back to start of the (next) page.

So, the group $(\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)},\hat\oplus)$ only needs one element as a generator: $(1,0)$, or moving to the “next” pixel (mostly, to the right). This means we’re guaranteed that every pixel on the screen is reachable. The ability to moving up or down is a nice addition, but not necessary.

However, defining the group with $\hat\oplus$ can get quite complicated. Nonetheless, let’s look at a simpler group $(\mathbb{Z}/wh\mathbb{Z},+)$, that is, a group of integers modulo $wh$ under a simple addition.

Why mention another group that seems unrelated to our focus group at all? Well, let’s compare the Cayley table of both groups. Starting with the group $(\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)},\hat\oplus)$:

\[\begin{array}{c|cc} \hat\oplus & (0,0) & (1,0) & \cdots & (w{-1},0) & \cdots & (w{-}1,h{-}1) \\ \hline (0,0) & (0,0) & (1,0) && (w{-}1,0) && (w{-}1,h{-}1) \\ (1,0) & (1,0) & (2,0) && (0,1) && (0,0) \\ \vdots &&& \ddots \\ (w{-}1,0) & (w{-}1,0) & (0,1) && (w{-}2,1) && (w{-}2,0) \\ \vdots &&&&& \ddots \\ (w{-}1,h{-}1) & (w{-}1,h{-}1) & (0,0) && (w{-}2,0) && (w{-}2,h{-}1) \end{array}\]Then, for the group $(\mathbb{Z}/wh\mathbb{Z},+)$:

\[\begin{array}{c|cc} + & 0 & 1 & \cdots & w{-}1 & \cdots & wh{-}1 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 1 && w{-}1 && wh{-}1 \\ 1 & 1 & 2 && w && 0 \\ \vdots &&& \ddots \\ w{-}1 & w{-}1 & w && 2w{-}2 && w{-}2 \\ \vdots &&&&& \ddots \\ wh{-}1 & wh{-}1 & 0 && w{-}2 && wh{-}2 \end{array}\]We can see that their structure are exactly the same!

In mathematical terms, we say that the group $(\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)},\hat\oplus)$ and $(\mathbb{Z}/wh\mathbb{Z},+)$ are isomorphic. That is, there exists a way to morph one group into another, and vice versa.

Thus, instead of coding the complicated $\hat\oplus$, we may just use the simpler model $(\mathbb{Z}/wh\mathbb{Z},+)$, result in this code:

(w,h) = (80,24)

fromCoord (x,y) = x + y*w

toCoord n = (\(y,x) -> (x,y)) $ divMod n w

move''' (x,y) ps = toCoord $ aux (fromCoord (x,y)) ps

where aux n [] = n `mod` (w*h)

aux n ('L':ms) = aux (n-1) ms

aux n ('R':ms) = aux (n+1) ms

aux n ('U':ms) = aux (n-w) ms

aux n ('D':ms) = aux (n+w) ms

Afterwards

The group $(\mathbb{Z}/wh\mathbb{Z},+)$ simplifies the model for pixel-character movement that row-increment wraparound. And, with a little modification, that’s also works for the column-increment wraparound too (hooray for Chinese, Japanese, and Korean).

However, we can’t have both row and column increment at the same time. Well, most of the time it still works, but weird things will happen around the corner of the screen. Take a look at an operator $\ddot\oplus$, whose try to increment both row and column,

\[\begin{bmatrix}x_1\\y_1\end{bmatrix} \:\ddot\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}x_2\\y_2\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} y_q+x_1+x_2\pmod{w} \\ x_q+y_1+y_2\pmod{h} \end{bmatrix},\]where

\[x_q = \left\lfloor\frac{x_1+x_2}{w}\right\rfloor \quad\quad\text{and}\quad\quad y_q = \left\lfloor\frac{y_1+y_2}{h}\right\rfloor.\]It is easy to see that

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix}w{-}1\\h{-}1\end{bmatrix} \:\ddot\oplus\: \left( \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} \:\ddot\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} \right) &= \begin{bmatrix}1\\1\end{bmatrix}, \\ \left( \begin{bmatrix}w{-}1\\h{-}1\end{bmatrix} \:\ddot\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} \right) \:\ddot\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix}, \\ \left( \begin{bmatrix}w{-}1\\h{-}1\end{bmatrix} \:\ddot\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} \right) \:\ddot\oplus\: \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix}. \end{align}\]That is, $(\mathbb{Z}_{(w,h)},\ddot\oplus)$ is no longer a group, let alone an abelian group.

Visually, the twisted torus would be too twisted that the bottom-right corner sometimes overlap with the top-left corner.

Not only can the cat be alive and dead at the same time, but she can also be in multiple boxes at once (until you observe).

We can’t be too greedy to wish for both!

References

- Artin, Michael. Algebra (2nd Edition). Pearson, 2010.

-

Because we’re com-sci students, a.k.a., Batman 🙃 ↩

-

Throughout this post, I’ll encode 2D coordinate as pairs and a column vectors interchangeably. The equivalent of those two objects is also true for most, if not all, textbooks dealing with this subject. ↩

-

Addition is not a good operator for introducing group theory anyway. Textbooks typically use matrix multiplication for teaching this subject, because it does not come with commutative property. ↩

-

In many other applications, not drawing the character when it’s out of bound is actually a good idea. But here, let’s pretend we wish to see our character on screen all the time. ↩

-

We, humanity, might not grasp the geometry of a torus intuitively. But who knows? Someday we might live in a giant spinning torus in the sky… ↩

-

For other groups, especially those with infinite elements, we need to allow the usage of inverse elements (without including the inverses themselves into the generators). For example, $(\mathbb{Z},+)$ may have $S=\lbrace1\rbrace$ as a generator, then produce negative integers through the only inverse. ↩

author