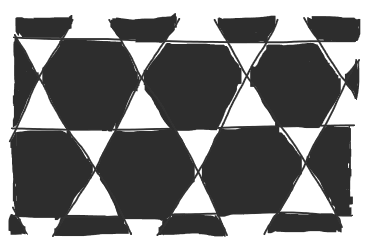

Checkerboard pattern for hexagonal tiling

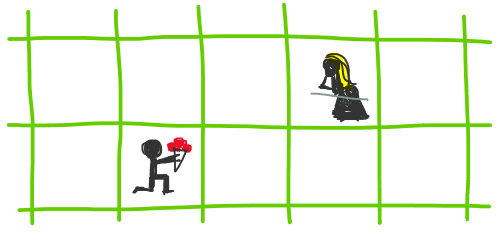

Consider a two-player game on a (possibly infinite) 2D square grid, where each player controls one piece on the board. The piece can move to any of the 4 adjacent tiles—left, right, up, or down (kinda like a king in chess, but without diagonal moves). Each turn, both players must move their pieces simultaneously; they can’t just stay on the same tile from the previous turn. Here’s a catch: if both pieces are on adjacent tiles and try to move into each other’s tiles at the same time, they don’t crash into each other midway; instead, they pass through. To win this game, both players must move their pieces onto the same tile at the same turn. Is this game winnable?

Can Romeo and Juliet ever met?

One might observe that the game is unwinnable in some scenarios. For example, when both pieces are spawned on adjacent tiles. Since game’s rule force both players to move every turn, they’ll keep passing each other forever.

Can we determine the winnability for far away pieces? Certainly! Just draw a path joining both pieces. The game is winnable iff the path’s length is even. Because, in each turn both players can alter the path length by an even amount. Thus, an odd path is never winnable, i.e., the distant between the two pieces can never reach zero.

Finding a path that joins the pieces can be mundane and prone to error, from human’s perspective. So, a quick and simple way to aid us humans is to color the grid with a checkerboard pattern.

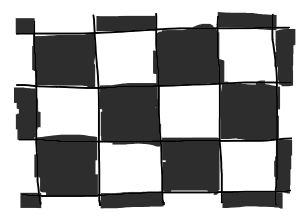

Standard checkerboard pattern for square tiling

Now we know right away whether the game is winnable or not: The game is winnable iff both pieces are spawned on tiles of the same color.

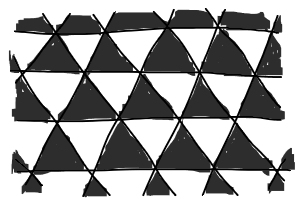

The square grid is nice, but what about the other grids / meshs / lattices / tessellations? Starting with the regular ones, we can see that the triangular tiling can be colored similarly to the checkerboard pattern too.

Triangular tiling, color with the even-odd pattern

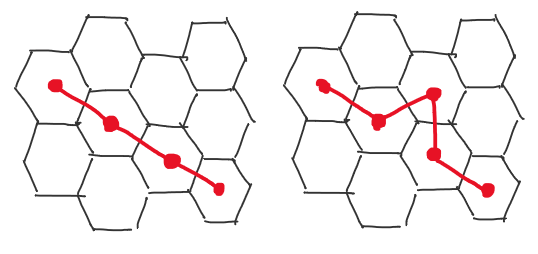

Sadly1, we cannot apply this pattern to the hexagonal tiling. This is because there can always be a path of even length joining any pair of tiles. To see this, consider a cluster of 3 hexagonal tiles– namely P, Q and R –connected to each other. A path from P to Q can be either of even or odd length: going straight from P to Q gives an odd path, but taking a detour via R results in an even path.

Same destination, different length: (left) odd path (right) even path

For semi-regular grids, we can apply the pattern to some of them.

Trihexagonal tiling, where triangles and hexagons mix together

What is the essence that determines the winnability of this game? Which properties do these cases have in common?

One way to do this is to view the tiling as a graph where each tile is a vertex; edges in the graph represent the sides joining two tiles in the original grid (which is, precisely, the dual graph). Thus, the original grid can be painted with the even-odd pattern iff its corresponding graph is bipartite (so, time to hone your depth-first search skills).

Or we can going back to the even-odd path length framework, but now we’re focused on a single tile and asking: does a cycle loop back to this tile is of odd length? And the answer is quite simple! Consider one corner of the tile. We can see that the odd cycle exists if this corner has an odd degree. Thus, the tiling can be painted in the even-odd pattern iff every corner has an even degree.

Even though the hexagonal tiling cannot be painted with the even-odd pattern, but can we not paint it with some “useful” checkerboard-like pattern at all?

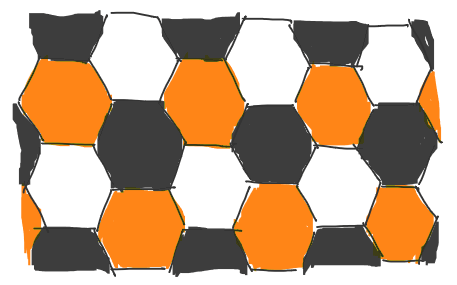

Looking back at its corners again, all of them have a degree of 3. What if we use 3 colors instead?

Hexagonal tiling, painted alternatively with 3 colors

We can see that this pattern encodes information that helps us find a way to win the game. If both players are spawned on tiles of different colors, then they should move to the 3rd color on the next turn. It also sheds light on the general case where there’re more than just two players: some game cannot be won in just one turn, although they are spawned closely together, because we cannot move everyone from 3 different colored tiles to met at the same tile in just one turn!

Beautiful!

-

Or rather, hooray! we can always win the game! ↩

author