$S_k(n) = 1^k + 2^k + 3^k + \cdots + n^k$

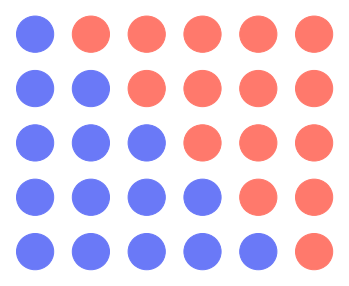

I’ve been wondering for quite a long time, what is the formula for the sum of integers to the power of a constant, $1^k + 2^k + 3^k + \cdots + n^k$, for every $k \in \mathbb{N}$. Take a look at the simplest case for $k=1$, we have a beautifully illustrated proof.

Proof without words that $1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots + n = n(n+1)/2$

By this visualization technique, we may also called the result a triangular number.

Though we, humanity, knows the formula since ancient Greek. However, legends (might be wrong) told that youngling Gauss can solve $1+2+3+\cdots+100$ quickly, despite that the teacher post this problem just to keep the students busy.

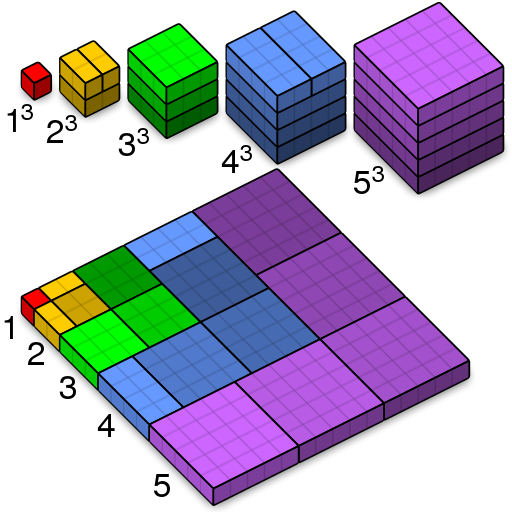

Back to the sum. For the case $k=2$ we also have an illustrated proof (and naming it).

Interactive proof without words that $1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 + \cdots + n^2 = n(n+1)(2n+1)/6$

The proof gives us a beautiful formula. Which, take the previous case into account, we might guess that the general formula can be written in the structure

\[S_k(n) \stackrel?= \frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)\cdots(???)}{(k+1)!}.\]But how can we know that this formula is correct? Keep in mind that the illustration technique has its own limitation. That is when we want to proof for the higher $k$, we have to consider $(k{+}1)$-dimensional space. Which most of us human cannot visualize it, right?

Proof without words that $1^3 + 2^3 + 3^3 + \cdots + n^3 = (1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots + n)^2$ – picture from Wikipedia

Ok, there are some workarounds to avoid higher dimensions than we may imagine. But those tricks seem to don’t scale well with the generalization. Thus, we have to ditch the illustration technique even though it’s quite a fun exercise.

Besides, just for the case of $k=3$, we can clearly see that the proposed formula is not anything close to the true nature of this sum 😭

So we have to tackle the equation head-on. Starts with the familiar binomial expansion

\[(a+1)^{k+1} = a^{k+1} + \binom{k+1}k a^k + \cdots + \binom{k+1}2 a^2 + \binom{k+1}1 a + 1.\]We define $f_k(a) = (a+1)^{k+1} - a^{k+1}$. Observe that we can handle $\sum f_k(a)$ in two different ways. The first way is using telescoping series to zoom the first term to the last term by negating intermediate terms,

\[\begin{align} \sum_{a=1}^n f_k(a) &= \left( (n+1)^{k+1} - n^{k+1} \right) + \cdots + \left( 3^{k+1} - 2^{k+1} \right) + \left( 2^{k+1} - 1 \right) \\ &= (n+1)^{k+1} - 1 \\ &= n^{k+1} + \binom{k+1}k n^k + \cdots + \binom{k+1}2 n^2 + \binom{k+1}1 n. \label{eq:telescope}\tag{1} \end{align}\]The other way is expanding each $f_k(a)$, then grouping terms with the same exponent,

\[\begin{align} \sum_{a=1}^n f_k(a) &= \sum_{a=1}^n \left( \binom{k+1}k a^k + \cdots + \binom{k+1}2 a^2 + \binom{k+1}1 a + 1 \right) \\ &= \binom{k+1}k \! \left( \sum_{a=1}^n a^k \right) + \cdots + \binom{k+1}1 \! \left( \sum_{a=1}^n a \right) + \left( \sum_{a=1}^n 1 \right) \\ &= \binom{k+1}k S_k(n) + \cdots + \binom{k+1}2 S_2(n) + \binom{k+1}1 S_1(n) + S_0(n). \label{eq:expansion}\tag{2} \end{align}\]Since we want to find $S_k(n)$ and now we have all the terms for the computation. We let $\eqref{eq:telescope} = \eqref{eq:expansion}$ and do some magic,

\[S_k(n) = \frac1{k+1} \left( \sum_{p=1}^{k+1} \binom{k+1}p n^p - \sum_{p=0}^{k-1} \binom{k+1}p S_p(n) \right). \label{eq:pascal}\tag{3}\]This is the technique and formula in the same manner as Blaise Pascal discovered in 1654 (no surprise he’s also known for the triangle). The formula hints us that, in order to find $S_k(n)$, we have to find $S_p(n)$ for all $p < k$ first.

It is natural to ask if we can drop the other $S_p(n)$ terms? Observe that, from the basis case $S_0(n) = n$, we may induct that the polynomial for $S_k(n)$ has degree $k+1$. So we’ll guess that the structure should rely on $\sum\binom{k+1}{p}n^p$ terms only, by dissolving terms in $\sum\binom{k+1}{p}S_p(n)$ into them. That is we want to adjust $\eqref{eq:pascal}$ into this structure

\[S_k(n) = \frac1{k+1} \left( \binom{k+1}{k+1} \boxed{?} n^{k+1} + \binom{k+1}k \boxed{?} n^k + \cdots + \binom{k+1}1 \boxed{?} n \right). \label{eq:guess}\tag{4}\]One way to do it is to expand terms from $\eqref{eq:pascal}$ and try to make them become $\eqref{eq:guess}$. By abusing the matrix notation, we may write

\[S_k(n) \cong \frac1{k+1} \begin{pmatrix} +\binom{k+1}{k+1} & +\binom{k+1}{k} & +\binom{k+1}{k-1} & +\binom{k+1}{k-2} & \cdots & +\binom{k+1}{1} \\ \boxed{\color{red}-\tbinom{k+1}{k-1}\times} & \boxed{S_{k-1}(n)} & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot \\ \boxed{\color{green}-\tbinom{k+1}{k-2}\times} && \boxed{S_{k-2}(n)} & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot \\ \boxed{\color{blue}-\tbinom{k+1}{k-3}\times} &&& \boxed{S_{k-3}(n)} & \cdot & \cdot \\ \vdots &&&& \ddots & \vdots \\ \boxed{-\tbinom{k+1}0\times} &&&&& \boxed{S_0(n)} \end{pmatrix} \! \begin{bmatrix} n^{k+1} \\ n^k \\ n^{k-1} \\ n^{k-2} \\ \vdots \\ n \end{bmatrix}.\]A left box in each row is a multiplier for their row. While a right box is $S_p(n)$ at the highest degree before expansion. This time, we’ll expand them with $\eqref{eq:guess}$. Which yields us the matrix

\[\begin{pmatrix} +\binom{k+1}{k+1} & +\binom{k+1}{k} & +\binom{k+1}{k-1} & +\binom{k+1}{k-2} & \cdots & +\binom{k+1}{1} \\ & {\color{red}-\binom{k+1}{k-1}}\frac1k\binom{k}{k}\boxed{?} & {\color{red}-\binom{k+1}{k-1}}\frac1k\binom{k}{k-1}\boxed{?} & {\color{red}-\binom{k+1}{k-1}}\frac1k\binom{k}{k-2}\boxed{?} & \cdot & {\color{red}-\binom{k+1}{k-1}}\frac1k\binom{k}{1}\boxed{?} \\ && {\color{green}-\binom{k+1}{k-2}}\frac1{k-1}\binom{k-1}{k-1}\boxed{?} & {\color{green}-\binom{k+1}{k-2}}\frac1{k-1}\binom{k-1}{k-2}\boxed{?} & \cdot & {\color{green}-\binom{k+1}{k-2}}\frac1{k-1}\binom{k-1}{1}\boxed{?} \\ &&& {\color{blue}-\binom{k+1}{k-3}}\frac1{k-2}\binom{k-2}{k-2}\boxed{?} & \cdot & {\color{blue}-\binom{k+1}{k-3}}\frac1{k-2}\binom{k-2}{1}\boxed{?} \\ &&&& \ddots & \vdots \\ &&&&& -\binom{k+1}0\frac11\binom11\boxed{?} \end{pmatrix}.\]

Observe that, except for the top row, each cell in the matrix starts with a negative coefficient $-\binom{k+1}{k-?}$. We want to convert this cell to have a positive coefficient $+\binom{k+1}{k-?}$, the cell in the top row of its own column.

For example, a cell $-\binom{k+1}{k-3}\frac1{k-2}\binom{k-2}{k-2}\boxed{?}$ (row 4, column 4) can be nudged to have a multiplier of $+\binom{k+1}{k-2}$ instead. Which might be done via this technique

\[\begin{align} \binom{k+1}{k-3}\frac1{k-2} &= \frac{(k+1)!}{(k-3)!4!} \frac1{k-2} \\ &= \frac{1\cdot2\cdot3\cdots(k+1)}{1\cdot2\cdots(k-3)\cdot{\color{blue}4}\cdot3\cdot2\cdot1} \frac{\color{red}(k-2)}{\color{red}(k-2)} \frac1{k-2} \\ &= \frac{1\cdot2\cdot3\cdots(k+1)}{1\cdot2\cdots(k-3)\cdot{\color{red}(k-2)}\cdot3\cdot2\cdot1} \frac{\color{red}(k-2)}{\color{blue}4} \frac1{k-2} \\ &= \frac{(k+1)!}{(k-2)!3!} \frac{(k-2)}4 \frac1{k-2} \\ &= \binom{k+1}{k-2} \frac14. \end{align}\]Done nudging and the matrix became

\[\begin{pmatrix} +\binom{k+1}{k+1} & \color{blue}+\binom{k+1}{k} & \color{red}+\binom{k+1}{k-1} & \color{green}+\binom{k+1}{k-2} & \cdots & +\binom{k+1}{1} \\ & {\color{blue}-\binom{k+1}{k}}\frac12\boxed{?} & {\color{red}-\binom{k+1}{k-1}}\boxed{?} & {\color{green}-\binom{k+1}{k-2}}\frac32\boxed{?} & \cdot & -\binom{k+1}{1}\frac12\binom{k}{1}\boxed{?} \\ && {\color{red}-\binom{k+1}{k-1}}\frac13\boxed{?} & {\color{green}-\binom{k+1}{k-2}}\boxed{?} & \cdot & -\binom{k+1}{1}\frac13\binom{k}{2}\boxed{?} \\ &&& {\color{green}-\binom{k+1}{k-2}}\frac14\boxed{?} & \cdot & -\binom{k+1}{1}\frac14\binom{k}{3}\boxed{?} \\ &&&& \ddots & \vdots \\ &&&&& -\binom{k+1}{1}\frac1{k+1}\binom{k}{k}\boxed{?} \end{pmatrix}.\]Don’t see its beauty yet? Well lets plug it back into the big picture equation

\[S_k(n) \cong \frac1{k+1} \begin{pmatrix} +1 & +1 & +1 & +1 & \cdots & +1 \\ & -\frac12\binom11\boxed{?} & -\frac12\binom21\boxed{?} & -\frac12\binom31\boxed{?} & \cdot & -\frac12\binom{k}{1}\boxed{?} \\ && -\frac13\binom22\boxed{?} & -\frac13\binom32\boxed{?} & \cdot & -\frac13\binom{k}{2}\boxed{?} \\ &&& -\frac14\binom33\boxed{?} & \cdot & -\frac14\binom{k}{3}\boxed{?} \\ &&&& \ddots & \vdots \\ &&&&& -\frac1{k+1}\binom{k}{k}\boxed{?} \end{pmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \binom{k+1}{k+1} n^{k+1} \\ \binom{k+1}{k} n^k \\ \binom{k+1}{k-1} n^{k-1} \\ \binom{k+1}{k-2} n^{k-2} \\ \vdots \\ \binom{k+1}{1} n \end{bmatrix}.\]

Observe that every cell with $\boxed{?}$ is multiplied by a constant. Thus, no matter how we scale the matrix by changing the value $k$; if we fill the same value into the same $\boxed{?}$, we will always get the same column sum.

And by induction, we find that each of $\boxed{?}$ has the same value as we expected. Hence, we arrived at the conclusion

\[S_k(n) \cong \frac1{k+1} \begin{pmatrix} +1 & +1 & +1 & +1 & \cdots & +1 \\ & -\frac12\binom11B_0 & -\frac12\binom21B_1 & -\frac12\binom31B_2 & \cdot & -\frac12\binom{k}{1}B_{k-1} \\ && -\frac13\binom22B_0 & -\frac13\binom32B_1 & \cdot & -\frac13\binom{k}{2}B_{k-2} \\ &&& -\frac14\binom33B_0 & \cdot & -\frac14\binom{k}{3}B_{k-3} \\ &&&& \ddots & \vdots \\ &&&&& -\frac1{k+1}\binom{k}{k}B_0 \end{pmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \binom{k+1}{k+1} n^{k+1} \\ \binom{k+1}{k} n^k \\ \binom{k+1}{k-1} n^{k-1} \\ \binom{k+1}{k-2} n^{k-2} \\ \vdots \\ \binom{k+1}{1} n \end{bmatrix} = \frac1{k+1} \begin{bmatrix} \binom{k+1}{k+1} B_0 n^{k+1} \\ \binom{k+1}k B_1 n^k \\ \binom{k+1}{k-1} B_2 n^{k-1} \\ \binom{k+1}{k-2} B_3 n^{k-2}\\ \cdots \\ \binom{k+1}1 B_k n \end{bmatrix}.\]

In other words,

\[S_k(n) = \frac1{k+1} \sum_{p=1}^{k+1} \binom{k+1}{p} B_{k+1-p} n^p. \label{eq:bernoulli}\tag{5}\]The constant $B_n$ is called the Bernoulli number, since the formula and constants were generalized by Jacob Bernoulli in the 1713 publication after his death.

Back to the matrix technique that leads to $\eqref{eq:bernoulli}$, we can calculate for $B_n$ with

\[B_n = 1 - \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \frac1{1+i} \binom{n}{i} B_{n-i}.\]Which has the very first values:

\[\begin{array}{c|ccccccccccccc} n & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 \\ \hline B_n & 1 & \frac12 & \frac16 & 0 & -\frac1{30} & 0 & \frac1{42} & 0 & -\frac1{30} & 0 & \frac5{66} & 0 & -\frac{691}{2730} \end{array}\]Even though the formula for $B_n$ is simple. But it requires manipulating lots of large numbers with lots of iterations. So it’s not an easy task for humans… Ada Lovelace, whom we considered the first programmer, published the world’s first computer program that calculated the constants in 1843.

Reference

- Nathaniel Larson, The Bernoulli Numbers: A Brief Primer

- Janet Beery, Sums of Powers of Positive Integers

- Roger B. Nelsen, Proofs Without Words II

author